Chapter I Early Work

Jane Gennaro was born in the Bronx in 1953, the second of six children within nine years, four born nine months after Valentine’s Day. Having moved to Long Island, their mother encouraged the children to play by drawing, building toy houses, constructing shrines for dead parakeets, and putting on shows, setting the stage for Gennaro’s remarkable creative virtuosity as a performing and visual artist.

Among the formative influences on her work that Gennaro has cited are her childhood discovery of nature and her Catholic upbringing, particularly the imagery of the first communion: the white dress, veil, and missal case. In her work there is a kind of yearning to preserve and imaginatively renew that which has been lost. Gennaro says, “Resurrection is a big part of what my work is about, as well as worship and forgiveness. I’m also fond of the ritualistic aspects of creating work with ephemeral materials. When I was little, I wanted to be a nun and/or a veterinarian and my work makes me feel like both.”

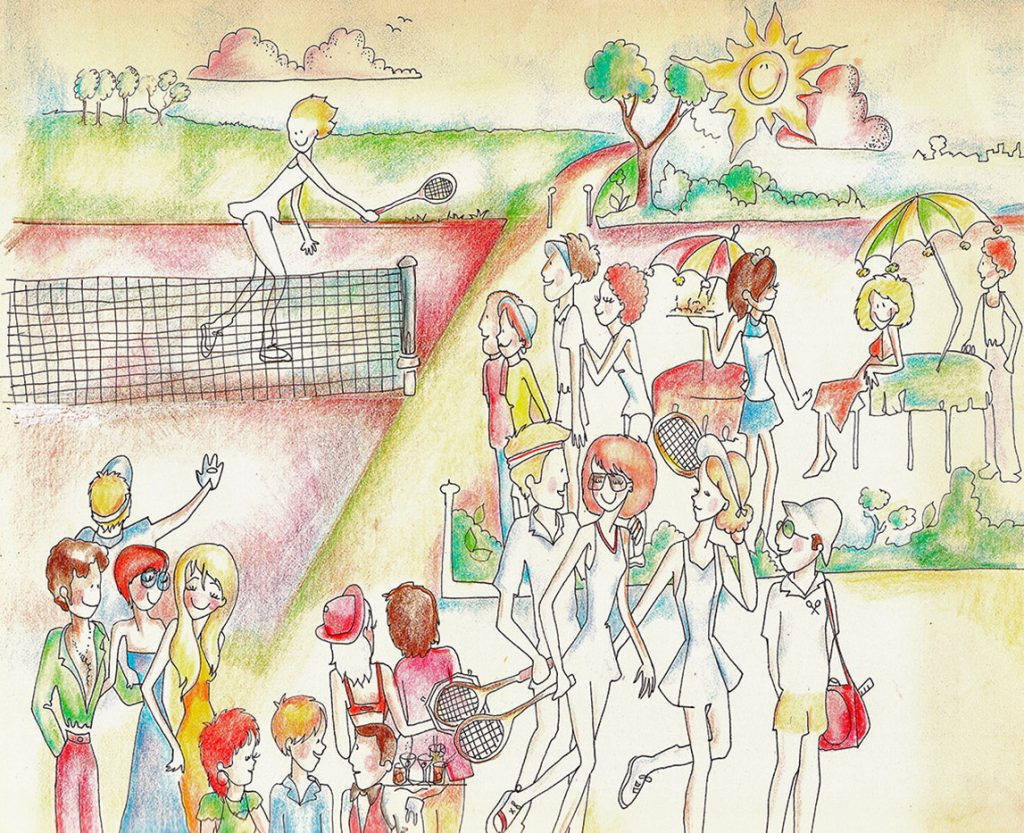

RAPIDOGRAPHS

Mr. Dehn, her high school art teacher, introduced her to her “new best friend” — the Rapidograph, a precision instrument for technical drawing with which she began to depict her classmates, creating an astonishingly precocious body of group portraits. Having dropped out of college, she found employment as a record company receptionist, where she relieved the boredom with an evolving gaggle of Rapidograph drawings of whatever happened to be happening. In due course, she was providing drawings to MAD magazine, Chappell Music and Barbara Jo Slate Inc. as a professional illustrator. “Clearly,” she bragged, “Me and my Rapidograph, we’re on the way to the top!” And she never put the pen down. As time went on, her pen-and-ink drawings became ever more ambitious and complex, and with the addition of color more intricate still.

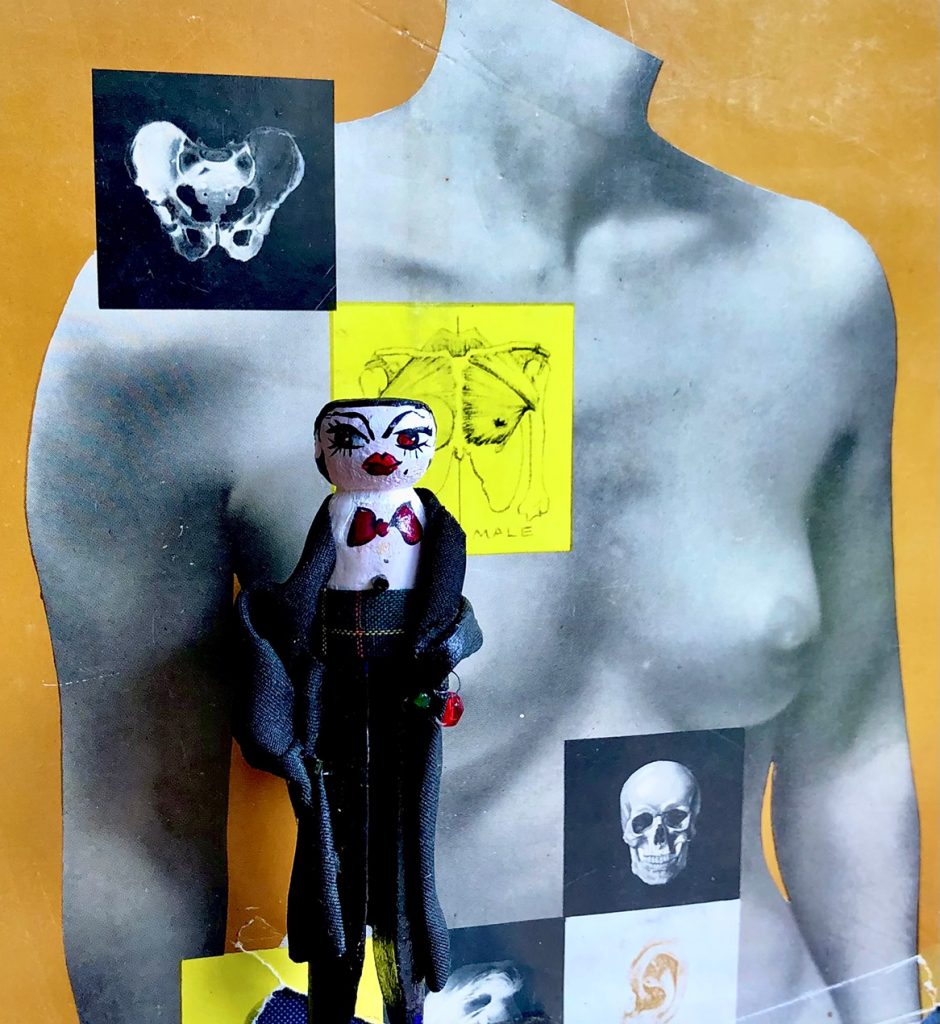

CLOTHESPIN DOLLS

In due course, Gennaro spun back to puppetry in Clothespin Dolls, a remarkable series of constructions that juxtaposed, in jarring fashion, cloyingly sentimental, wittily attired dolls with bitterly ironic stock imagery, setting the stage for her later, more refined three-dimensional explorations.

HAIR

First came the series Hair, which uses the artist’s own hair as the medium for creating linear structures in the mode of automatic drawing. Gennaro then created complex, articulated networks, fantastic worlds that are part human and part creature. Each drawing is a moving mass of interconnected shapes and beings, with a surreal, dream-like quality, suggesting that the body and identity are mutable elements in a larger network of relationships — in the words of critic John Mendelsohn, “A floating graphic super-organism.”